The Returning Salmon of Piper’s Creek Watershed

Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) at in Piper’s Creek at Carkeek Park in Seattle, Washington (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis / Our Wild Puget Sound)

History of salmon in the Piper’s Creek watershed

There’s a special kind of buzz around the Pacific Northwest in the fall when our creeks come alive with salmon fighting to make it upstream to spawn. We get to watch as these giant athletes emerge from the saltwater depths to the shallowest streams in our communities to dig their redds, lay their eggs, and usher in the next generation.

One of the best locations for viewing this event in its natural form is at Piper’s Creek in Carkeek Park; right in the heart of Seattle on the ancestral lands of the Duwamish tribe, who originally named the creek “Dropped Down”, or qWátub.

Piper’s Creek supported robust runs of coho, chum, steelhead and cutthroat until the last known spawning pair of wild salmon were seen in 1927 after years of logging, over-fishing, and urbanization. The creek is still plagued by issues from urbanization as most of the land in the creek’s watershed is now made up of impervious surfaces, such as buildings, roads, sidewalks and parking lots, forcing stormwater runoff and leaking sewer lines to run toward the creek, greatly degrading the water quality with pollutants.

Luckily, in 1979, initiatives such as the Carkeek Watershed Community Action Project (CWCAP) began with a mission to improve the health of the watershed and restore the salmon runs to Piper’s Creek. Together with the Suquamish Tribe, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Seattle Parks, and Seattle Public Utilities salmon runs have been reestablished in Piper’s Creek through reintroduction programs

When to view salmon in Piper’s Creek

The chum and coho runs at Carkeek Park generally start in late October and run through early December. Carkeek Park Salmon Stewards is a great resource for monitoring when the fish have arrived and they also provide great volunteer opportunities for getting involved with the restoration of these inspiring fish.

How to view salmon at Carkeek Park

Piper’s Creek and Venema Creek meander through Carkeek’s 200-acre park, offering plenty of up-close viewing opportunities. Parking is available along the creek, making it easy to explore and figure out where the fish are on any given day.

Starting at the lower parking lot the trail runs west all the way to Puget Sound or east to a small bridge that goes over Venema Creek. Piper’s Creek carries on west for a short distance until it’s rerouted underground through 300+ feet of concrete pipe that act as a total fish barrier, blocking nearly two miles of potential salmon habitat upstream. Chum and coho can be found gathering at this barrier, making for a prime viewing location, but also a stark reminder of the work left to be done at Piper’s Creek and how big of an impact barriers big and small can have on the spawning success of our local salmon.

Don’t live near Carkeek Park?

Don’t worry, we have you covered with a map of salmon viewing locations in the Puget Sound watershed!

What you’ll see during the salmon runs

Species

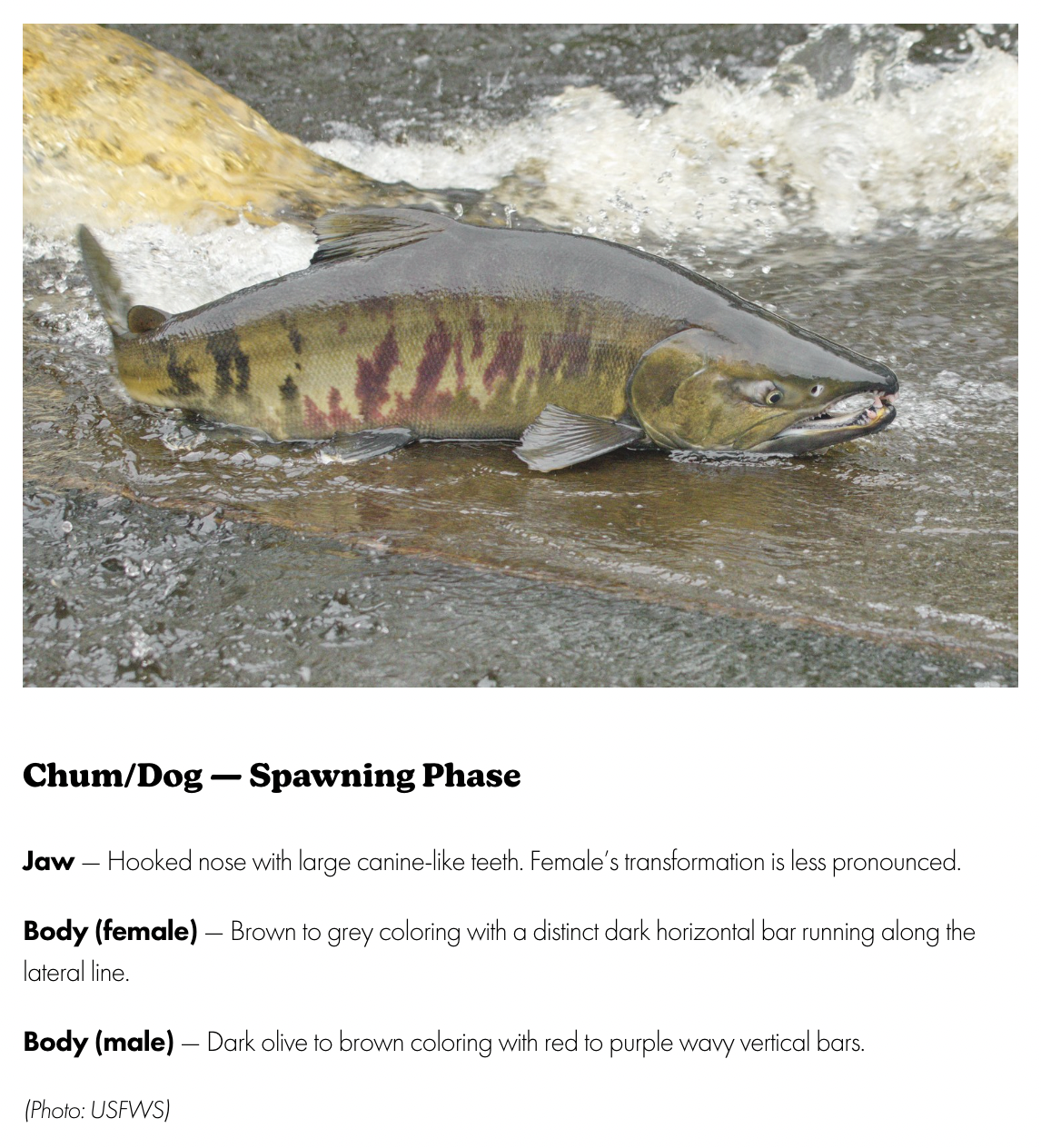

The most common species of salmon to see in Piper’s Creek is chum, which were chosen to repopulate Piper’s Creek specifically for the limited amount of time they spend in freshwater, making them less susceptible to the impacts of pollution build up in urban streams. Coho salmon and resident cutthroat trout have also reestablished in smaller numbers on their own, although over 50% of coho die before spawning, which is likely due to the degraded water quality and heightened levels of metals and toxins.

There’s an upward trajectory here, though, as restoration efforts continue and environmental policy changes in favor of cleaner, healthier alternatives. 2022 saw 975 returning chum and 153 returning coho through December, marking the highest year on record.

Behavior

These fish are returning from their lives in the sea (up to seven years for the chum and only 18 months for the coho) to Piper’s Creek in order to compete for the best mates and the best nesting in order to spawn and bring on the next generation of salmon. Because of that you’re likely to see a lot of interesting spawning behavior.

Fighting — Spawning is a contentious time for salmon and there’s a lot of competition going on between individuals. Males will fight each other to assert dominance and to fend off others, using their giant teeth to latch on to each other. While in a redd with a female the males will continually cross over the female to watch for incoming males. Females will also fight with each other when defending their redds and can get pretty feisty when another female gets close.

Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) competing in a redd at Carkeek Park (Video: Sara Montour Lewis / Our Wild Puget Sound)

Digging — The female’s job in spawning is to dig redds to deposit her eggs, so you’ll likely see a lot of digging behavior. They’ll test certain spots to see if it’s ideal for laying eggs, they’ll excavate the entire redd to prep it for the eggs, and then they also do digging behavior after spawning to cover the eggs.

A female chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) digging a redd in Piper’s Creek (Video: Sara Montour Lewis / Our Wild Puget Sound)

Spawning — Spawning behavior looks a lot like digging, except this time the female is using the same general movements to deposit her eggs into the redd so the male can fertilize them. You may also notice a quivering, vibrating motion from the male, which encourage the female to start laying.

A male and female pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) spawning together in a redd (Video: Sara Montour Lewis / Our Wild Puget Sound)

Egg-laying — The eggs are the main event! The entire reason for this arduous journey as these tiny spheres will transform into the next generation of salmon and we will hopefully see them return again in 3-7 years, carrying on the evolution of this incredible species. It’s important to keep this in perspective as you’re viewing and to tread lightly whenever you’re exploring around salmon creeks. You never know where exactly these precious eggs will be hiding underfoot, both immediately after fish spawn and for months afterwards as they’re developing, so it’s the best practice to keep kiddos and doggos out of known salmon creeks so we can protect them. They could even be underneath the light gravel on the banks as our river depths change with rainfall and tide changes at lower elevations.

Bright pink salmon eggs in a riverbed in the Puget Sound watershed (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis / Our Wild Puget Sound)

Death — While it’s not quite as fun to talk about, here in the Pacific our five species of salmon all don’t survive after spawning. We know there are varying degrees of emotions tied to seeing this, from shock + horror to sadness to fascination to elation that they completed their life cycle.

We like to stick to the fascination to elation side of the spectrum and we wanted to talk a little bit about why.

We know that our Pacific salmon populations face a complete gauntlet, from the moment they’re laid as eggs to the moment they get back to their natal creeks for their turn to spawn.

Post-spawned salmon on the side of the river banks not only feed our forests and the creatures all along the way, but they truly lived their fullest life. They somehow survived the delicate egg to fry stages, avoiding predators + contamination along their way out to sea.

While at sea they found enough food to eat and oxygen to breathe, they dodged predators like other fish, sharks, seals, sea lions, our beloved Southern Resident Killer Whales, and humans as they avoided our own fishing nets + lines.

When they finally were big enough to make the journey back they made it through manmade blockages and bottlenecks and another gauntlet of predators to make it to their natal streams where they fought others in their own species for the chance at reproducing and giving life to the next generation.

So! Next time you see a salmon on the riverbank and your instinct is to feel sadness, remind yourself of this incredible journey that took sheer determination and will power to pull off. These individuals lived their fullest lives and it’s hard to be anything but inspired by that.

A chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) at the end of its life cycle in Piper’s Creek (Photo: Sara Montour Lewis / Our Wild Puget Sound)

References

Carkeek Watershed Community Action Project — “History of Salmon in Piper’s Creek Watershed”

Seattle Times — “Carkeek Park, celebrating its 75th birthday, has seen some hard times”

WDFW — “Viewing Chum Salmon”